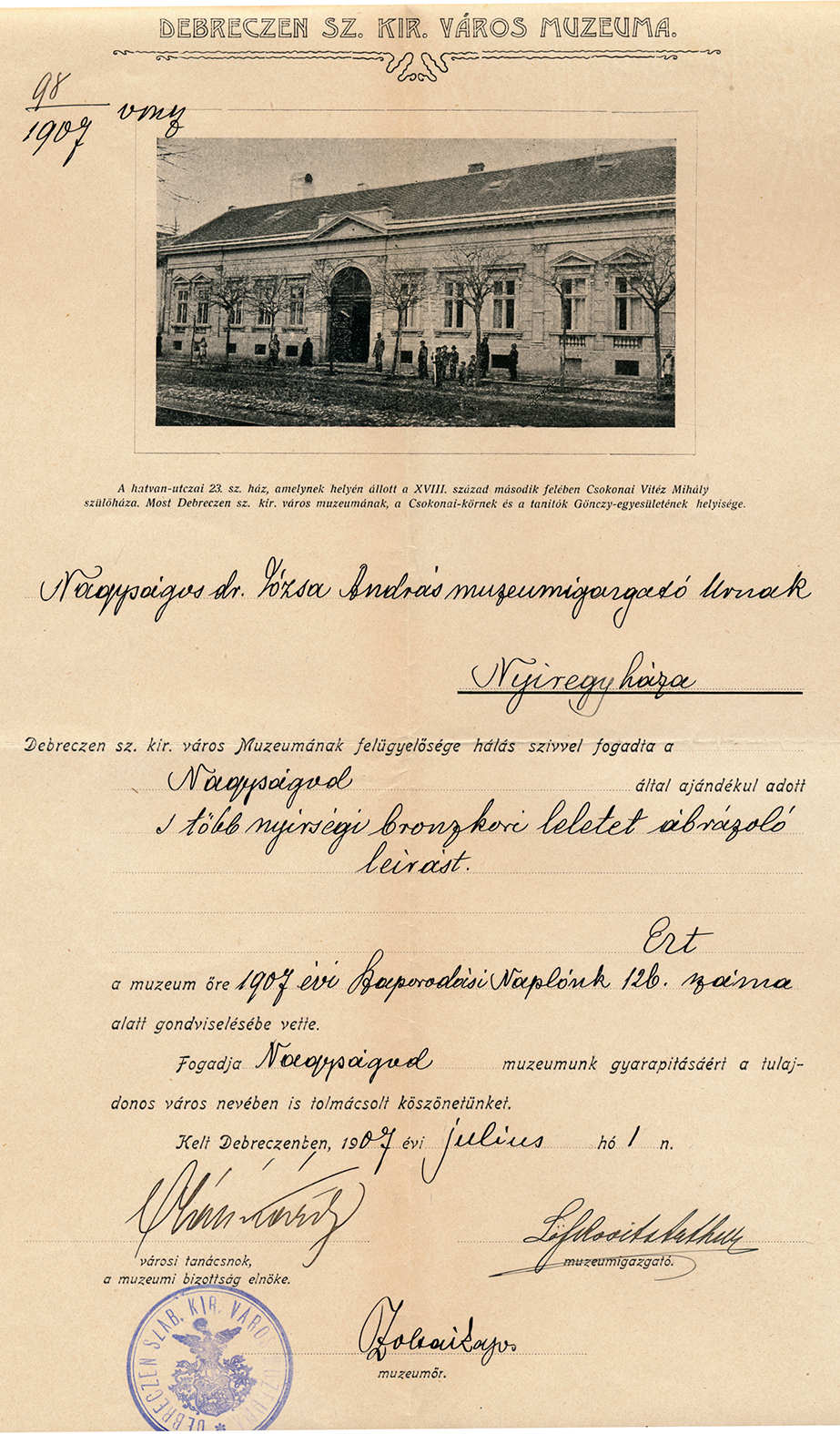

If we consider the fact that the founder of the museum, András Jósa, died in 1918, it may be a surprise to learn that the archives of Jósa András Museum contain many photocopied drawings from his lifetime.

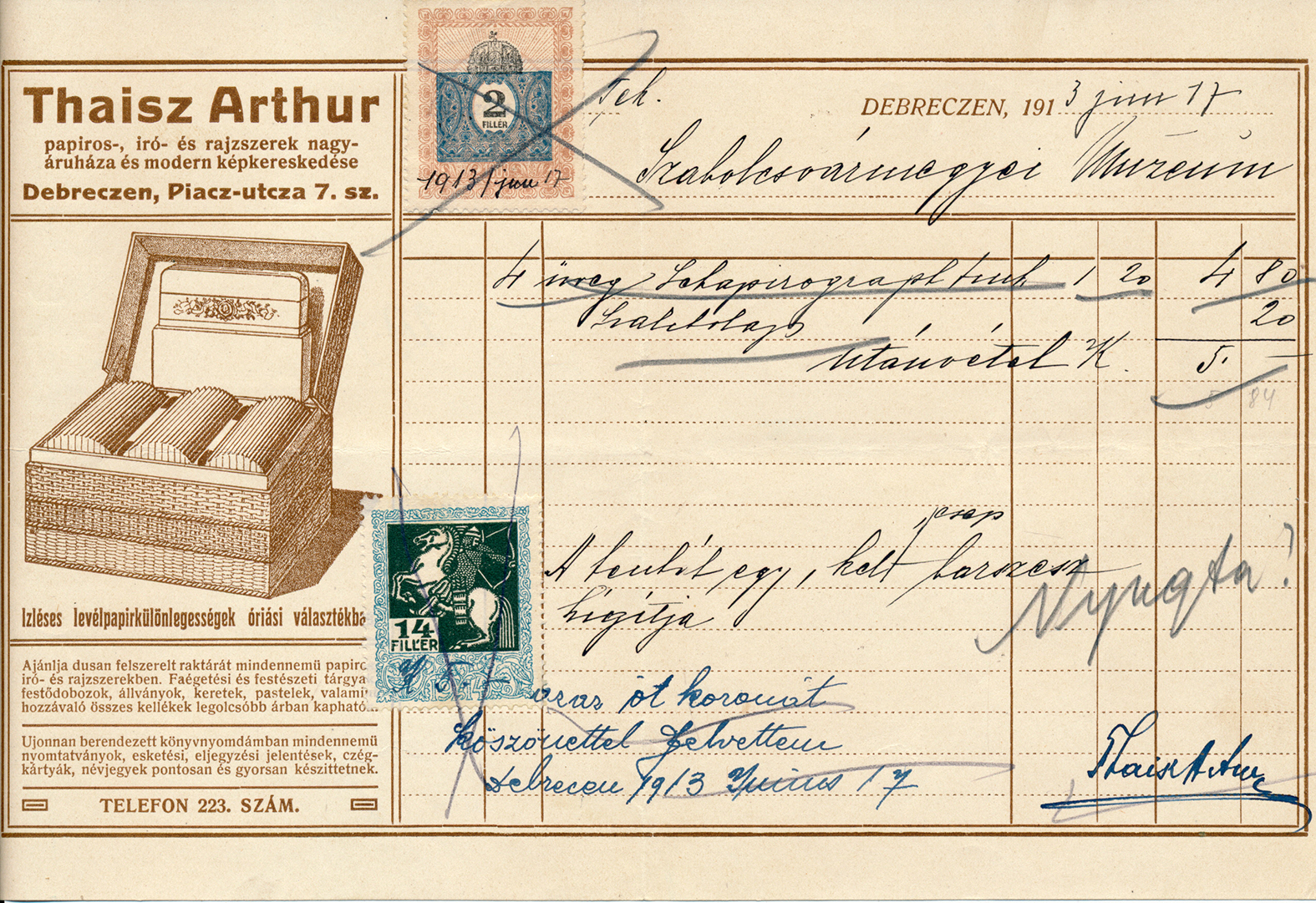

In 1913, the 69-year old András Jósa purchased a Schapirograph duplicating machine for the price of 39 crown 34 fillers (which was 13% of the museum’s annual budget)

It is worth considering that the first copy machine was patented by David Gestetner in 1880. The development of the innovation started immediately. However, it is noteworthy that only three decades after the first patent in London, in 1913, a copy machine already operated in the museum in Nyíregyháza.

The first photocopying method was stencilling. The illustrations to be reproduced were redrawn with special pens on special paper. Each page was copied separately. The stencil paper was smeared in paint. The speed of copying and the number of the copies were limited.

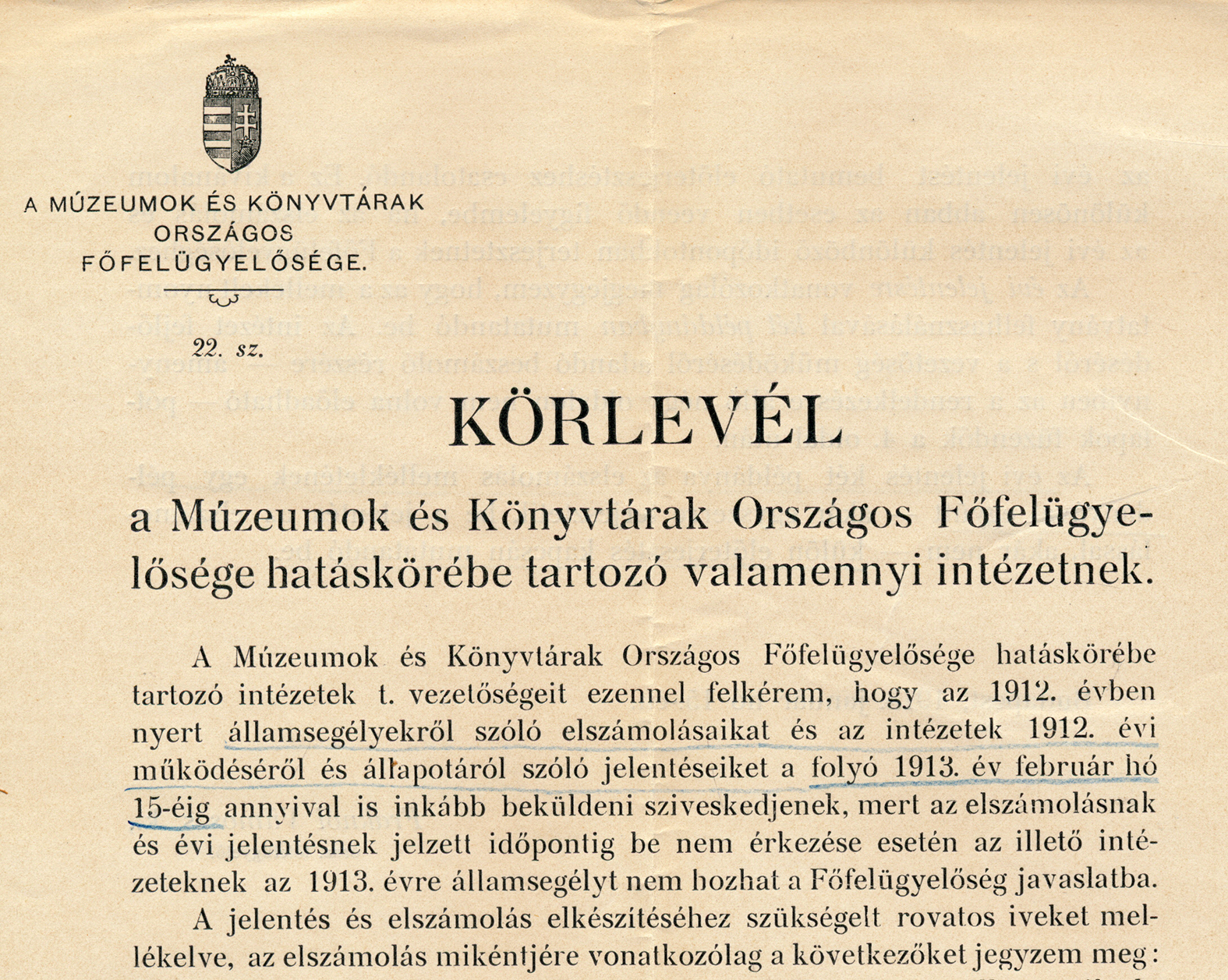

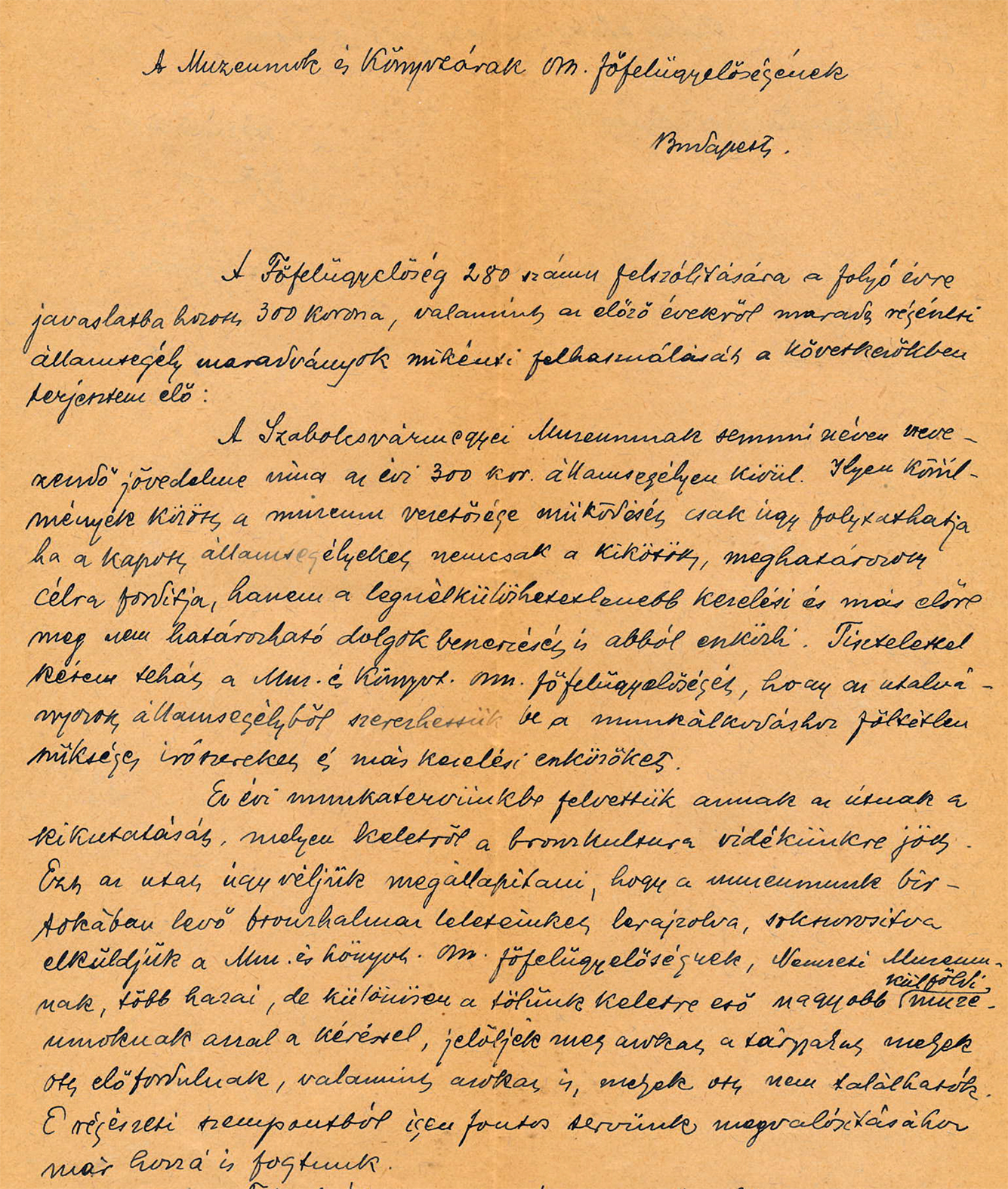

The copy machine was financed from the remaining money from the only source of the museum which was insured by the state, in a form of a subsidy. The state aid in those times was provided through The General Inspectorate of Museums and Libraries and a strict account of its spending was expected from the museum guard, as the person in charge responsible for running and developing the museum was called in those times.

András Jósa, the director of the museum, personally applied for the permission of the Insectorate in Pest to purchase the copy machine. In addition to the copy machine, duplicating disk, special ink and paper for the machine are also included in the account.

Jósa’s most highly valued collection was the treasures of the Bronze Age. He was proud of being able to collect such a rich collection. He was interested in the origin of these items, and he wondered whether they were the products of a culture which he preferred to call „Culture of the Nyírség Region”. This was the reason why –according to his statement– by 1915 „We have drawn and duplicated in 60 copies almost 2000 items made of bronze.” This was complemented by the drawings of the pots of the Bronze Age placed in a table, which was finally copied in many examples and sent to experts throughout the country and abroad to find about the possible whereabouts of similar objects.

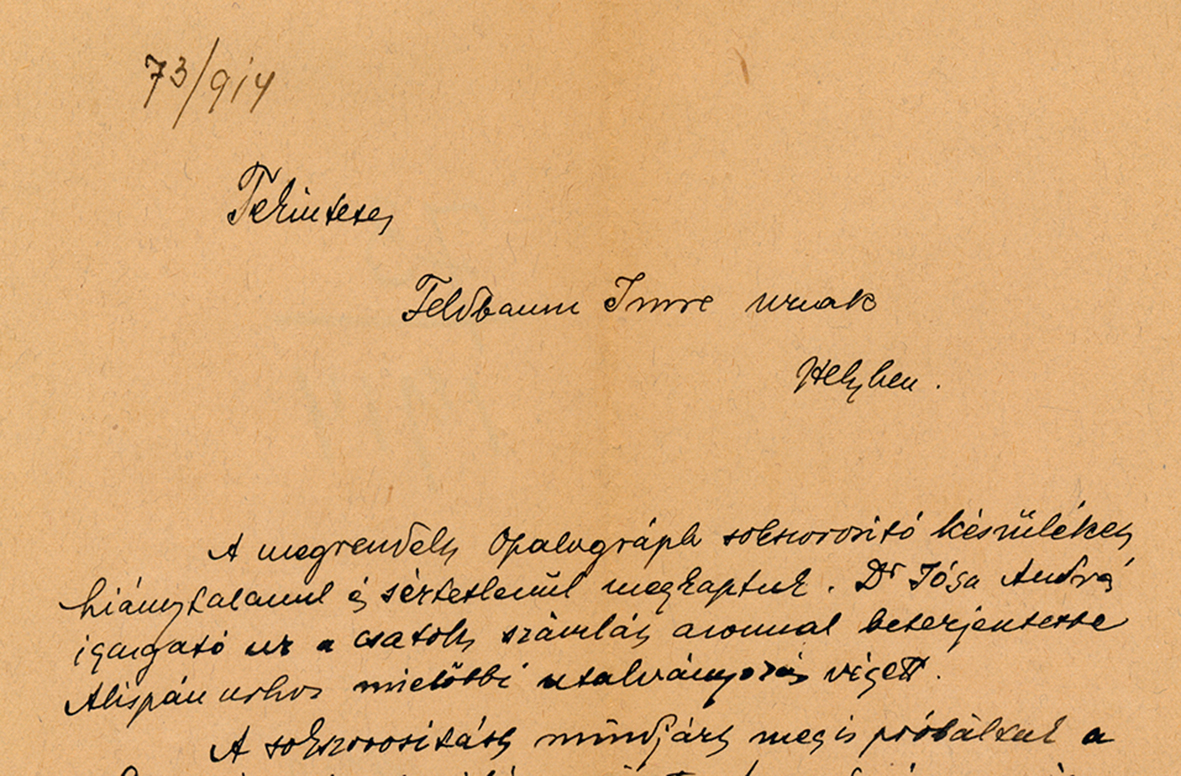

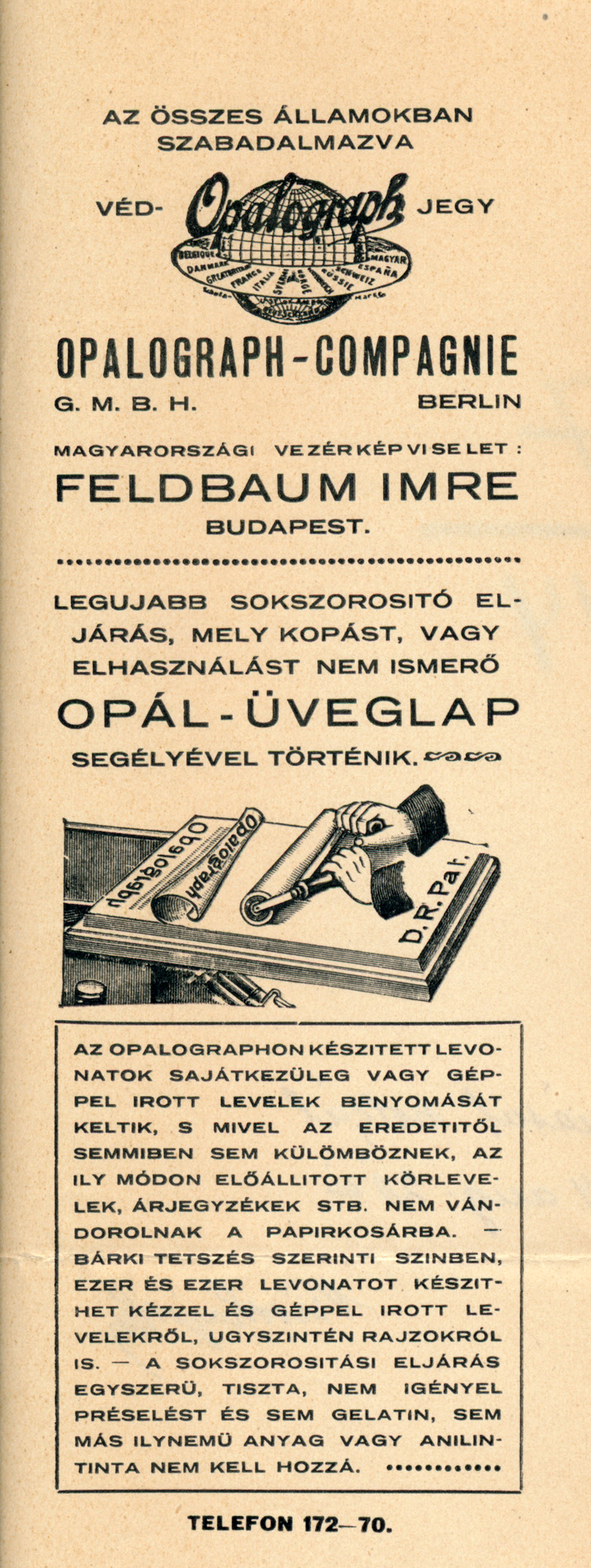

The photocopy machine proved to be useful. In 1914 Jósa enquires about a new type of machine, called Opalograph, asking for test prints.

The test prints were of good quality, so they ordered the machine for 100 Crowns and according to a letter they put it into function immediately.